Writing A Ray Tracer in Go - Part 2

This is part 2 of my journey to try and write a ray/path tracer in Go. Checkout part 1 here.

I’m roughly following the e-book Ray Tracing in One Weekend, but translating all of the code into Go.

In the previous post we covered how a path tracer works and got an image to display on the screen by blending red, green and blue into a cool looking gradient. This time around we’ll draw a sphere instead, but by actually sending rays into the scene and marking the pixels where they hit the object.

This is the first major step into building a fully functional path tracer. Lets get to it.

All of the code for this post can be found on my Github.

Rays

Every ray/path tracer has one thing in common, a way to model a ray. A ray is defined as:

In geometry, a ray is a line with a single endpoint (or point of origin) that extends infinitely in one direction.

So, a ray has two parts: origin and direction.

We can model this in our code by defining a struct like so:

type Ray struct {

Origin, Direction Vector

}Next, we need to be able to move along our ray either forward or backward. The function to allow us to do so is defined as: p(t) = A + t * B where A is the ray origin, B is the ray direction, and t is a real number.

In code, this looks like:

func (r Ray) Point(t float64) Vector {

b := r.Direction.MultiplyScalar(t)

a := r.Origin

return a.Add(b)

}This method takes in a t as a float64 and returns a position vector in 3D space, which is our new position on our ray.

Adding a Sphere

Now that we can define and move along a ray, we need to add the second piece of the puzzle, a sphere.

In geometry a sphere is defined as having a center and radius.

We can model this in Go with another simple struct:

type Sphere struct {

Center Vector

Radius float64

}Now comes the fun part, adding the ability for a ray to determine whether or not it comes in contact with a sphere.

Intersecting with the Sphere

note: Math ahead. I had trouble remembering a lot of this from algebra/geometry class, so if like me you need a refresher, this link may come in handy.*

The book goes into greater detail, however the basic formula for determining if a point is on a sphere is as follows:

dot((p - C),(p - C)) = R * R

Where p is the point, C is the center of our sphere, and R is the sphere radius.

Now this is great, but we want to know if our ray p(t) = A + t * B ever hits the sphere anywhere. So basically, is there any t for which p(t) satisfies the sphere equation.

This corresponds to:

dot((p(t) - C),(p(t) - C)) = R * R

Which expands to:

dot((A + t * B - C),(A + t * B - C)) = R * R

Expanding and moving all terms to the LHS, we get:

t * t * dot(B, B) + 2 * t * dot(A-C, A-C) + dot(C, C)

Since this is quadratic, we can use the quadratic formula to solve for t. When solving the quadratic, there is the discriminant portion of the equation (b * b - 4ac) which tells us the number of solutions.

If the discriminant is:

- positive - there are 2 real solutions

- negative - there are 0 real solutions

- zero - there is 1 real solution

All this boils down to the following method:

func (r Ray) HitSphere(s Sphere) bool {

oc := r.Origin.Subtract(s.Center)

a := r.Direction.Dot(r.Direction)

b := 2.0 * oc.Dot(r.Direction)

c := oc.Dot(oc) - s.Radius*s.Radius

discriminant := b*b - 4*a*c

return discriminant > 0

}Adding Color

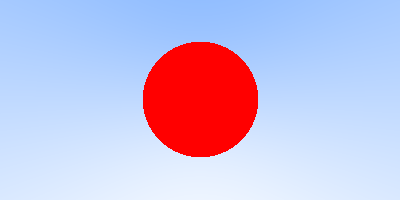

Now that we can determine if our rays hit our sphere, lets add some color. We want our image to show that when a ray does hit the sphere the pixel is marked red, and when they don’t, it shows up as a nice blue gradient.

Again the book goes into greater detail on how this is done, but I tried to comment the Color method as best I could:

func (r Ray) Color() Vector {

sphere := Sphere{Center: Vector{0, 0, -1}, Radius: 0.5}

if r.HitSphere(sphere) {

return Vector{1.0, 0.0, 0.0} // red

}

// make unit vector so y is between -1.0 and 1.0

unitDirection := r.Direction.Normalize()

// scale t to be between 0.0 and 1.0

t := 0.5 * (unitDirection.Y + 1.0)

// linear blend

// blended_value = (1 - t) * white + t * blue

white := Vector{1.0, 1.0, 1.0}

blue := Vector{0.5, 0.7, 1.0}

return white.MultiplyScalar(1.0 - t).Add(blue.MultiplyScalar(t))

}Putting it All Together

After updating our code to use these new methods, running the program via go run *.go yields the out.ppm file which gives us:

Note the jagged edges of the sphere, this is because we haven’t implemented anti-aliasing yet, so the pixel is either red or part of the background (there is no blending happening). We’re going to fix this in a later edition.

Well, that’s enough for now. Next time we’ll work on shading and add another object to the scene.

Update: Part 3 is available here: Writing A Ray Tracer in Go - Part 3